|

Home |

|

History |

|

Meetings |

|

Articles |

|

Book Reviews |

|

Annual Coin Show |

|

Join |

|

Links |

|

Contact us |

Miniature Vignettes

by Roger H. Durand

Reprinted from Paper Money, Vol. XIX, Whole No. 90

Early Engravers

From the time of the earliest banknotes around the turn of the 19th century, engravers have striven at their art, attempting to decorate their works with as elaborate vignettes as their skills can produce. The very early engravers, such as Reed, Amos Doolittle, Peter Maverick, and others of lesser prominence, created the complete note design. Their skills were not always equal to the task.

For instance, although some were experts on letters or numerals, their crude early vignettes left much to be desired. The cows, fishes and other natural and symbolic devices were barely identifiable in some cases. These early vignettes did perform one important service and that was to make the notes more difficult to counterfeit. However, the racketeers soon became as proficient in their work as the original engravers were and those early vignettes were no longer effective in stopping counterfeiting.

As time passed, the engravers improved their skills, so that by the early 19th century their work was vastly improved. The first plates were done entirely by hand, but later machinery played a large role in the creation of bank note printing surfaces.

New Techniques in Engraving

Shortly after the turn of the century, a New Englander named Jacob Perkins invented a method for constructing bank note plates out of several small parts enclosed in a frame and bolted together so they would not move during the printing process. This Perkins process became very popular, with several banks opting for it. The earliest notes had no vignettes at all, just the necessary printing and denomination numerals. Of course, these notes were readily counterfeited.

As time went on, Perkins did add crude vignettes to the notes’ designs but still the counterfeiters were not foiled. Some of these later Perkins process notes had rather elaborate vignettes covering as much as a third of the face design. Eventually this system became obsolete, the craftsmen in the engraving industry once again flourished, and their products truly became works of art. In some cases, numerals were made by engraving machines following geometric designs, with the balance of the plates hand engraved. Eventually the plates were again completely done by hand but not by one artist only.

The Art on Bank Notes

About the time that the Durand brothers, Asher and Cyrus, came on the scene, bank note engraving had become an art of specialists. Several engravers combined their talents to create notes that were certainly beautiful, to say the least. One engraver would specialize in lettering, another in numerals, and still another in vignettes. The results of their combined talents were notes that were comparatively difficult to counterfeit.

With the exception of a few men like W.L. Ormsby, who engraved such lavish vignettes that they covered the entire note in some cases with numerals and lettering overlaid the main pictorial design, bank note engravers worked as teams and formed companies with the different engravers as partners. Some vignettes engravers were vain, as great artists become, and actually signed the vignette on the note. The lesser engravers were reduced to the menial task of producing background, borders and other inconsequential parts of the designs. The small vignettes used on several different places on notes as fill in the overall design were probably done by these apprentice novice engravers.

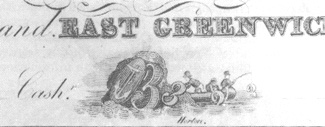

Most all the later bank notes had small “miniature vignettes” between the signatures. A careful study of these small vignettes demonstrates that some of them had more interesting subjects than the main vignettes. Usually a glass is needed to appreciate the labor involved to create the fine work on such small scale. When you stop to think that these vignettes were all handmade, it is a wonder that such fine detail was achieved.

About the Note—Fishing for Three’s

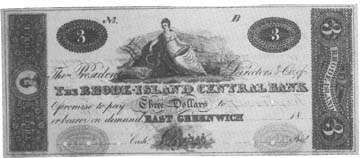

Illustrated here is a $3 Rhode Island Central Bank of East Greenwich note which was probably engraved around 1817 by a man named Horton. It is unclear whether he worked alone. If, indeed, the note was done by one person, it would have been created at the end of the era of single engravers.

Fishing for Three’s

The miniature vignette at the bottom center of the above note was untitled but it could well be entitled “Fishing for Three’s”.

Close examination shows that behind the main figure of Ceres is a small boat with three fishermen fishing “threes” in numeral form out of the water. Probably the “three” that Ceres is touching with the scythe came from this source. The entire theme ties together the fishing and farming industries that predominated in Rhode Island at the time. The shadow on the two signature spaces was caused by the bleeding of the numeral dies from the attached note on the sheet when it was folded over. It is not part of the note design. No signed notes are known from this series. To my knowledge, this note is unique.

Suggested References

Philatelic and numismatic literature is replete with references to the art and history of bank note engraving. Readers are referred to the entire 37-year run of The Essay-Proof Journal for a varied fare of biographies, business histories, and technical information. To a lesser extent, Paper Money has printed a variety of articles on similar themes, especially in the pre-1976 issues.

For more detail on the life and work of Jacob Perkins, see Jacob Perkins, His Inventions, His Times & His Contemporaries, by G. & D. Bathe, published by the Historical Society of Pennsylvania in 1942. The Story of the American Bank Note Company, the corporation’s own publication by William H. Griffiths which appeared in 1959, is also useful.