|

Home |

|

History |

|

Meetings |

|

Articles |

|

Book Reviews |

|

Annual Coin Show |

|

Join |

|

Links |

|

Contact us |

Obsolete Oddities

The “Frog” Notes of Windham, Conn.

The Battle of the Frogs

With a population of about a thousand inhabitants, Windham was one of the leading towns of the day. The times were hard, though. A disease had recently struck the town, and the French and Indians were a constant threat. Rumors of massacres and atrocities ran rampant while many of the men were away fighting the French or with Putnam fighting Indians. Windhamites often thought about the possibility of an attack, so it’s no surprise that on a hot, dark, June night in 1754 they thought their worst suspicions had come true. What they expected and what actually did happen, however, are two different things.

A black servant of parson White’s named Pomp was returning home around midnight, after seeing a lady friend at a nearby farm house. As he walked down the dark road, he neared the Windham Green. It was there he began to hear a strange and terrifying sound echoing through the night air. The noise seemed to come from everywhere at once. Pomp rushed home to awaken his master, shrieking all the way. Parson White then proceeded to sound the alarm, waking those who had not already been aroused by this awful sound or by the screaming of Pomp. As the noise continued, most thought it was an Indian ritual and by morning they would surely all be dead.

People began running about. Women shrieked, children cried, and men prepared for battle as the strange and mournful sound continued. A makeshift, ragtag army assembled on the green. Men were running about armed with pitchforks, knives, clubs and old swords, while a few actually had guns. Confusion and fear swept the village as the Windhamites listened and waited. Some claimed to have heard the savages calling, “We’ll have Colonel Dyer, Colonel Dyer, Elderkin too, Elderkin too.” Well, both Elderkin and Dyer were prominent lawyers in Windham who had recently planned a colonization project in the Susquehanna Valley, which would greatly irritate the Indians. This scared the townspeople even more. Many claimed to have distinguished Indian chants and drums among the noise. Others said there was nothing on earth that could make such an outlandish commotion and contended that it could only mean one thing; it is the judgment day and nothing could be done to save them except prayer. They waited and waited, expecting that they would all be dead by morning, but the savage army never appeared.

Colonel Dyer, Colonel Elderkin and a Mr. Gray then rode their horses up Mullin Hill toward the strange sound to determine just what it was. As they approached a small pond, they found that this was the source of the commotion. Some reports contend that the three actually fired shots toward the pond. Whatever happened that night is not clear but what they found were—thousands of dead and dying frogs, some still making their war cries. No one is sure why the frogs died. The theory held at the time was that they died fighting each other, possibly for the small amount of water in the lowered pond.

When the three men returned and reported their find, the townspeople were humiliated. “Some were pleased, and some were mad, some turned it off with laughter, and some would never hear a word about the thing thereafter. Some vowed that if the De’il himself should come they would flee him, and if a frog they ever met, pretend not to see him.” Although the area did not have a newspaper, the story quickly spread from town to town and eventually across the land. Windhamites became the butt of jokes and lawyers in particular were harassed with the bullfrog story. Even the clergy couldn’t help but laugh as indicated in this early reference to the frog battle, in a private letter from Reverend Stiles of Woodstock to his nephew, a law student:

Woodstock, July 9, 1754

“If the late tragical tidings from Windham deserve credit, as doubtless they do, it will then concern the gentlemen of your Jurisprutian order to be fortified against the dreadful croaks of Taurean Legions. Legions terrible as the very wreck of matter, and the crash of worlds. Antiquity relates that the elephant fears the mouse. A hero trembles at the crowing of a cock, but pray whence is it that the croaking of a bullfrog should so Belshazzerize a lawyer?

“Dyerful ye alarm made by these audacious, long winded croakers. Things unattempted yet in prose or rhyme, Tauranean terrors in Chimeras Dyer. I hope sir, from the Dyerful reports from the frog pond, you’ll gain some instruction, as well as from the report of my Lord Cook.”

As the years wore on, future generations learned to take the jokes and eventually became proud of the incident. This strange event was now an important part of Windham’s history, which should not be forgotten. It has since been immortalized in poetry and song, such as “Lawyers and Bull Frogs” and “The Epic of Windham”, and to top it off, a frog eventually became the central figure of the town seal.

The “Frog” Notes

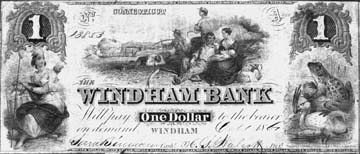

The Windham Bank was chartered in 1832 and opened in what is now known as Windham Center. Its business was small and development slow. The first bank notes issued by it are currently unlisted and are extremely rare. The only denominations I know of are one, three, and five dollars. Later on, the bank issued new notes, all of which have a vignette of a frog standing over the dead body of another frog. The frog vignette appears on the $1, $2, $3, $5 and $10 notes in the lower right corner. The old notes reminded everyone that touched them about the then-famous battle of the frogs, as exemplified by this poem by the Reverend Theron Brown, a famous Windham poet:

I pause to nurse a quaint remembrance here,

The bank and I were born the self same year.

I mind its notes, between whose figures poked,

Two frogs—so lifelike that they almost croked.

The original greenbacks of the native race,

That long anticipated Salmon Chase.

They blossomed like pond lilies from the mud,

Memento of a war that shed no blood.

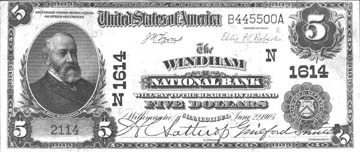

(Large Size) $5 National Currency Note, Charter #1614 of the Windham National Bank in Willimantic. The note bears the signatures of H. Clinton Lathrop and Guilford Smith, two prominent Windham residents.

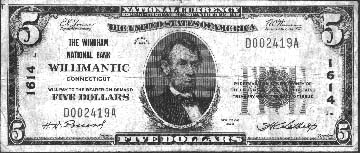

$5 National Currency Note shows the name Willimantic larger and is an example of the small-size Nationals of Windham.

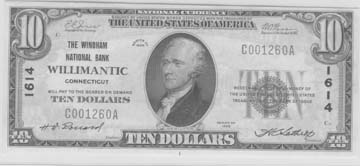

$10 National Currency Note, Charter #1614 of the Windham National Bank in Willimantic. This note is in much better condition. It is uncirculated and as fresh as if it was printed this morning.

THIS TABLET IS ERECTED BY

ANNE WOOD ELDERKIN CHAPTER, DAR

TO COMMEMORATE THE LEGEND OF THE BATTLE

OF THE FROGS

MRS. FRANK LARRABEE, REGENT

There are varied accounts of what actually happened that dark night in 1754. Whether the tale is an accurate description of that night’s events or is blown all out of proportion may never be known. But the legend of the battle of the frogs will forever come to life whenever someone is shown a note from the Windham Bank.

References:

1. Higbee, Lillian Marsh. Bacchus of Windham and the Frog Fight, 1930. (Source of quotations).

2. Larned, Ellen D. History of Windham County Connecticut, Wrocester, Mass. Charles Hamilton, 1874.

3. Todd, Charles Burr. In Olde Connecticut. New York, the Grafton Press, 1906.

4. Harpin, Mathias P. Harpin’s Connecticut Almanac. Harpin’s American Heritage Foundation, Inc., Jewett City, CT, 1976.