|

Home |

|

History |

|

Meetings |

|

Articles |

|

Book Reviews |

|

Annual Coin Show |

|

Join |

|

Links |

|

Contact us |

IN SEARCH OF . . .

A portrait of the first President of the United States

on state or federal U.S. paper money.

If you think I should look no further than my wallet, you’re wrong. The fact is, what I seek is not in my wallet, nor is it in yours. What is in my wallet is a one-dollar bill which bears a portrait of one George Washington. Who could this man be? Why should his portrait grace the face of this Federal Reserve note? Why couldn’t we have chosen someone of importance, such as, let’s say, the first President of the United States? That would have been a good choice.

My search for the answer has taken me through pages of various, revered paper money references. What I have found in most cases is a portrait on some obsolete issue here, a silver certificate there, and various other instruments of exchange of this man George Washington. Too often the worded description of the note claims this man was the first President of the United States. How could this be?

A lot of men and some women have been honored for their contribution to history by being portrayed on issues of U.S. paper money. Washington was one of them. He was a humble but aristocratic man who had to be prevailed upon to accept his term of the presidency. He served his country well and we have honored him for that achievement ever since. It is not the intent of this article to discredit this man. On the contrary, it is to introduce another very well-respected person of the time who is surely not as well known.

The Continental Congress first convened on September 25th, 1774. The last of its 22 sessions was on March 2nd, 1789. Fifteen different men presided over one or more sessions during this period. The purpose of the Congress was the formation of the Union which led to American independence. The document readied and signed by the representatives of this body were the Articles of Association prepared on Oct. 20, 1774.

On June 16th, 1775 George Washington, a Virginian, was nominated by John Adams of Massachusetts to be the commander of the Continental Army. On the following day Washington accepted amid a plea for no pay beyond his expenses. (After eight years of personal record keeping he submitted his statement to treasury accountants who, after auditing the same, found an error of only 80/ of one dollar due him over the amount claimed.)

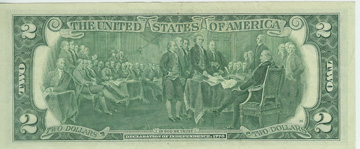

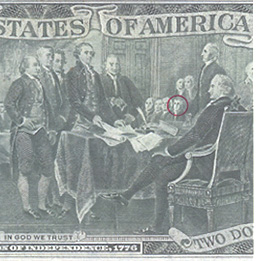

On June 7th, 1776 Richard Henry Lee of Virginia offered a resolution to Congress that became the foundation of the Declaration of Independence. This resolution was formed, adopted, and finally signed by most delegates by August 26th , 1776. The first printing was signed on July 4th, but only by John Hancock and attested to by Charles Thomson as Secretary of Congress. The presentation of the Declaration of Independence by Thomas Jefferson to John Hancock became the subject of John Trumbull’s famous painting of this event. (Trumbull took great pride in being able to reproduce the exact likeness of each delegate present at that session.) In this famous painting we can see the likeness of the future first President of the United States.

On June 12th, 1776 a committee of one member from each of the 13 colonies was named to prepare a document of confederation. The committee was dominated by John Dickinson of Delaware and article 1 of the draft stated, the name of this Confederacy shall be “The United States of America.” This new document, “The Articles of Confederation” had to be ratified by each colony before it could become law. During the next few years this document was rewritten and gradually ratified by each colony, the last being Maryland on March 1st, 1781 during the 10th session of the Continental Congress presided over by its 7th president.

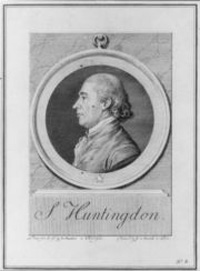

Huntington’s tenure with the presidency commended on September 28, 1779. He was succeeded by Thomas McKean of Delaware on July 105h, 1781. With Maryland’s ratification of the Articles of Confederation on March 1st, 1781 the last step had been taken for the congress to model itself as “The United States in Congress Assembled.” This was the birth of the United States of America. Samuel Huntington, President of the Congress, on that day became the first President of the United States of America. The presidential title would be assumed by George Washington eight years and 10 presidents later. Those Presidents of the United States who preceded Washington were:

Huntington’s tenure with the presidency commended on September 28, 1779. He was succeeded by Thomas McKean of Delaware on July 105h, 1781. With Maryland’s ratification of the Articles of Confederation on March 1st, 1781 the last step had been taken for the congress to model itself as “The United States in Congress Assembled.” This was the birth of the United States of America. Samuel Huntington, President of the Congress, on that day became the first President of the United States of America. The presidential title would be assumed by George Washington eight years and 10 presidents later. Those Presidents of the United States who preceded Washington were:

1. Samuel Huntington, Windham, CT. President of the Continental Congress September 28, 1779 to July 10th, 1781. During his tenure on March 1st, 1781 Maryland’s ratification of the Articles of Confederation effectively gave birth to a new union thus changing Mr. Huntington’s title to the First President of the United States.

2. Thomas McKean of Delaware was second to serve as President of the new nation. His term was from July 10th, 1781 to November 5th, 1781.

3. John Hanson of Maryland was third to serve his country in the presidential capacity. His term was from November 5th, 1781 to November 4th, 1782.

4. Elias Budinot of New Jersey was the fourth to serve under the Articles of Confederation. His term was from November 4th, 1782 to November 3rd, 1783.

5. Thomas Mifflin of Pennsylvania was the fifth person to serve. His term was from November 3rd, 1783 to November 30th, 1784.

6. Richard Henry Lee of Virginia served November 30th, 1784 to November 23rd, 1785.

7. John Hancock of Massachusetts was seventh to be elected. Due to ill health he was not able to perform his duties. He was however a previous President of the Continental Congress holding office from May 24th, 1775 to September 27th, 1777. This was before the “Articles” were ratified and the United States was still a colony.

8. Nathaniel Gorham of Massachusetts was eighth to serve as President. His term was from June 6th, 1786 to February 2nd, 1787.

9. Arthur St. Clair of Pennsylvania was the ninth President of the United States. His term was from February 2nd, 1787 to January 22nd, 1788.

10. Cyrus Griffin of Virginia was the 10th person to serve. His term was from January 22, 1788 to March 2nd, 1789.

On April 30, 1789, the electors of the Continental Congress met and elected the 11th President of the United States. George Washington, with the authority and powers granted by the new Constitution, took the reins of this Republic and skillfully guided it for the next eight years.

The rest is history.

Huntington’s portrait doesn’t appear on any issue of federal currency but his likeness does appear on the backs of two issues that display an engraved copy of John Trumbull’s painting, the presentation of the Declaration of Independence. One note bearing this engraving is the $100 first charter national bank note. The other is the small-size two dollar Federal Reserve note series of 1976, the so-called “Bicentennial Note.”

Huntington’s portrait doesn’t appear on any issue of federal currency but his likeness does appear on the backs of two issues that display an engraved copy of John Trumbull’s painting, the presentation of the Declaration of Independence. One note bearing this engraving is the $100 first charter national bank note. The other is the small-size two dollar Federal Reserve note series of 1976, the so-called “Bicentennial Note.”

Between the standing delegates at the table but in the background are four seated figures. The delegate seated at the right is Samuel Huntington. From this engraving it is possible to examine the exactness of facial expressions Trumbull was able to capture not only with Huntington’s likeness but with other delegates as well.

Between the standing delegates at the table but in the background are four seated figures. The delegate seated at the right is Samuel Huntington. From this engraving it is possible to examine the exactness of facial expressions Trumbull was able to capture not only with Huntington’s likeness but with other delegates as well.Quite a few examples of Trumbull’s painting appear engraved on state bank issues of the 1800s. While most of these are not all-encompassing of the complete painting, most, due to the strategic seating arrangement offered by Trumbull, do show the likeness of the first President.

It seems unusual though, that the portrait of Huntington has not yet been verified as appearing on any state bank note issues. He was also the Governor of Connecticut for ten years and, as a signatory of the Declaration of Independence, one would think at least be equal in fame to his contemporaries who do appear on these issues.

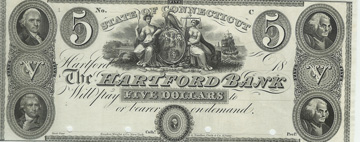

The obvious place to search for his portrait would be among the many issues of Connecticut obsolete paper money. Many of these issues of the 1820s and the 1830s bear portraits of John Jay (sixth President of the Continental Congress), Eli Whitney (inventor of the cotton gin and weapons manufacturer), Col. Jeremiah Wadsworth (Hartford’s most influential citizen of the time), John Hancock (a President of the Continental Congress and Governor of Massachusetts), and many other notables of that period.

While Washington’s portrait is the most commonly found on state and federal paper money of the United States, it is the author’s opinion that many other notable members of Congress and the judiciary deserve recognition for the part they played in the formation of this country. If we choose to honor Washington because of his contribution to the country while commanding the Continental Army, so be it. But if we want to adorn our paper money with a portrait of the first President, I think we have overlooked a most important figure. President Samuel Huntington should be the only person qualified for that title.

Be that as it may, I cannot point an accusatory finger at any of the editors and authors of our numismatic and syngraphic literature when, in fact, our own history books, probably without exception, confirm the notion that the portrait of our first President appears on various issues of U.S. paper money.

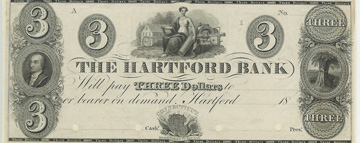

The illustrated note above from the state chartered Hartford Bank bears two unidentified portraits on the left side. The lower left portrait shows strong resemblance to Col. Jeremiah Wadsworth of Hartford, the moving fugure in the establishment of the Hartford Bank and a confidant of Alexander Hamilton. Wadsworth was a prominent mover of many early banks and savings institutions. During 1785-86 he was president of the Bank of New York. He was also the largest single stockholder in the Bank of North America and a director of the Bank of the United States.The upper left portrait cannot be identified by the author. It is most likely a Connecticut Statesman. Could this be the missing portrait I am in search of?

The person whose portrait most often appears on issues of state and federal currency is George Washington. He is generally regarded as being the first President of this country. However, this title should more aptly signify that he was the first elected President, elected to serve under the Constitution, which gave the office of the presidency more executive power. The presidency, under the "Articles", while being the highest in the land, was not a very influential or powerful one.

A large size silver certificate, series 1923, might well have looked like this had the portrait of the First President of the United States appeared on it.

The presentation of the signing of the Declaration of Independence became a popular vignette to use on many of this country's obsolete state bank issues as shown here on the example of the Bunker Hill Bank one dollar note of Charlestown, Massachusetts. This shows an abreviated version of the vignette. However, due to the strategic seating arrangements in Trumbull's original painting, the likeness of our first President, Samuel Huntington is evident. He is seated fourth from the left in the center of the vignette.

The portrait of John Jay, the first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States appears on this bill from The Hartford Bank. When Jay was appointed Minister to Spain Samuel Huntington was unanimously elected President of the Congress. The date was September 28, 1799

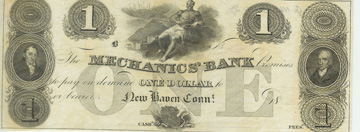

Eli Whitney (Pictured on the left on the above note) inventor, and James Hillshouse (on the right), politician and businessman, both were contemporaries of Samuel Huntington and have their portraits in prominence on Connecticut state issued private bank notes. Not a single portrait of Huntington has yet been posititvely identified on any obsolete note.

SOURCES

Casey, R.R. The Declaration of Independence. NY: Illustrated Pub.

Collier, C. and J. Lincoln. (1987). Decision in Philadelphia. NY: Ballantine Books.

Durand, R. (1992). lnteresting Notes About History. Privately printed.

Fielding, M. (1974). Dictionary of American Painters, Sculptors & Engravers. Green Farms, CT: Modern Books and Crafts, Inc.

Gerlach, L. (1976). Connecticut Congressman: Samuel Huntington, 1731-1796. Hartford, CT: American Revolution Bicentennial Commission of Connecticut.

Hessler, G. (1922). The Comprehensive Catalogue of U.S. Paper Money. Port Clinton, OH: BNR Press.

The National Archives. (1962). The Formation of a Union. Washington, DC: Publication #53-15.

The World Almanac Book of Facts. (1988). NY: Pharos Books.

Waugh, A.E. (1968). Samuel Huntington and His Family. Stonington, CT: Pequot Press.