|

Home |

|

History |

|

Meetings |

|

Articles |

|

Book Reviews |

|

Annual Coin Show |

|

Join |

|

Links |

|

Contact us |

Odd Denominations Were Normal Then !

What we consider odd denomination today were issued due to specific needs of the community or area that they circulated in. Whether it was due to foreign exchange rates for pounds, shillings, liras, franc, guilders or any other currency that immigrants were familiar with and used locally or that was used in trade with various countries or some manufacturer or business issuing its own notes to make buying a $7.00 item easier or a manís weekly wage of $8.00, the reasons are varied.

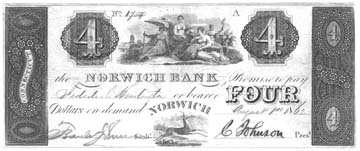

Pictured is a $4 note of the Norwich Bank of Norwich, Connecticut. During the early to mid 1800s denomination such as this were often encountered in various parts of the country. There are hundreds of denominations known. Included are the ones we are most familiar with. The $1, $5, $10, $20, $50 and $100, as well as the not too often encountered $2 bill.

Additionally there were $3, $4, $6, $7, $8, $9, $11, $12, $13, $14, $15, $25, $35, $40, $65, $75 etc. Of course if you were more affluent you might have in your wallet $200, $300, $400, $500, $750, $1,000, $5,000, $10,000 notes from among the higher denominations available. For the person of low to average means, one could encounter a note of $1.01 or $1.50 or $1.56.

Fortunately not all denominations circulated in the same geographical area. Notes were issued to meet the needs of their customers and depositors by the bank, merchant or manufacturer who issued the notes. Basically what it all boils down to is if there was a need for a particular denomination it was issued. Today notes seem pretty boring when you compare them to the good old days.